How Does the Memory Management Unit (MMU) Work with the Unix/Linux Kernel?

Understanding how your CPU's MMU collaborates with the Linux kernel to create process isolation, memory protection, and the illusion of infinite RAM.

When you write a program that allocates memory with malloc() or maps a file with mmap(), a fascinating dance occurs between hardware and software that most programmers never see. At the heart of this interaction lies the Memory Management Unit (MMU), a piece of hardware that works closely with the Unix/Linux kernel to create the illusion that each process has its own private memory space.

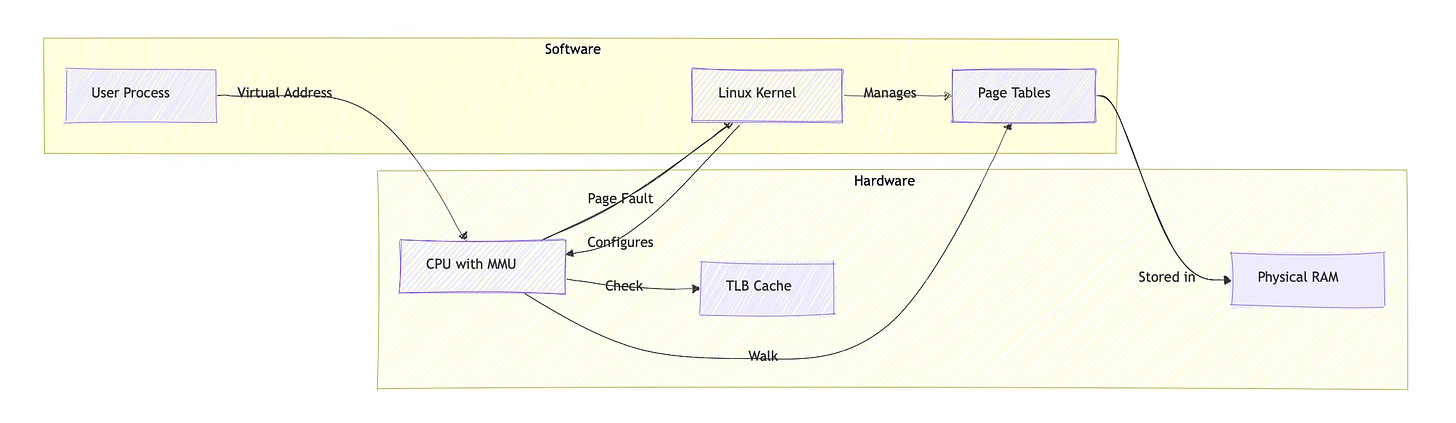

Many developers harbor misconceptions about the MMU's role. Some believe it's part of the kernel itself, while others think the kernel performs all address translations in software. The reality is more nuanced: the MMU is a hardware component, typically integrated into the CPU, that performs the actual address translation, while the kernel acts as its configurator and manager.

Understanding this relationship is crucial for system programmers, kernel developers, and anyone debugging memory-related issues. The MMU and kernel work together to provide virtual memory, process isolation, and efficient memory management, features that form the foundation of modern Unix-like operating systems.

Overview of the MMU and Memory Management

The Memory Management Unit serves as a hardware translator between the virtual addresses your programs use and the physical addresses where data actually resides in RAM. Think of it as an extremely fast address book that converts every memory reference your program makes.

Virtual memory provides several critical benefits. First, it gives each process the illusion of having access to a large, contiguous address space, even when physical memory is fragmented or limited. Second, it enables process isolation, basically one process cannot accidentally (or maliciously) access another process's memory. Third, it allows the system to use secondary storage as an extension of physical memory through swapping.

The MMU is a hardware component, not software. On most modern architectures, it's integrated directly into the CPU alongside the cache controllers and execution units. This hardware implementation is essential for performance, translating virtual addresses to physical addresses happens on every memory access, potentially billions of times per second.

When your program accesses memory at address 0x400000, the MMU immediately translates this virtual address to whatever physical address actually contains your data. This translation happens transparently and at hardware speed, making virtual memory practical for real-world use.

MMU and the Unix/Linux Kernel

The relationship between the MMU and kernel often confuses developers. The MMU is hardware, while the kernel is software that configures and manages that hardware. The kernel doesn't perform address translation, the MMU does that autonomously for every memory access.

The kernel's role is to set up the data structures that the MMU uses for translation. These data structures, called page tables, live in main memory and contain the mapping information the MMU needs. When a process starts, the kernel allocates and initializes page tables for that process, then tells the MMU where to find them.

Consider what happens when you call fork(). The kernel creates new page tables for the child process, often using copy-on-write semantics to share physical pages initially. The kernel configures these page tables, but the MMU performs all subsequent address translations using the information the kernel provided.

The distinction is important: kernel data structures like vm_area_struct in Linux track memory regions at a high level, while page tables contain the detailed mappings the MMU actually uses. The kernel manages both, but the MMU only directly interacts with page tables.

Address Translation Mechanics

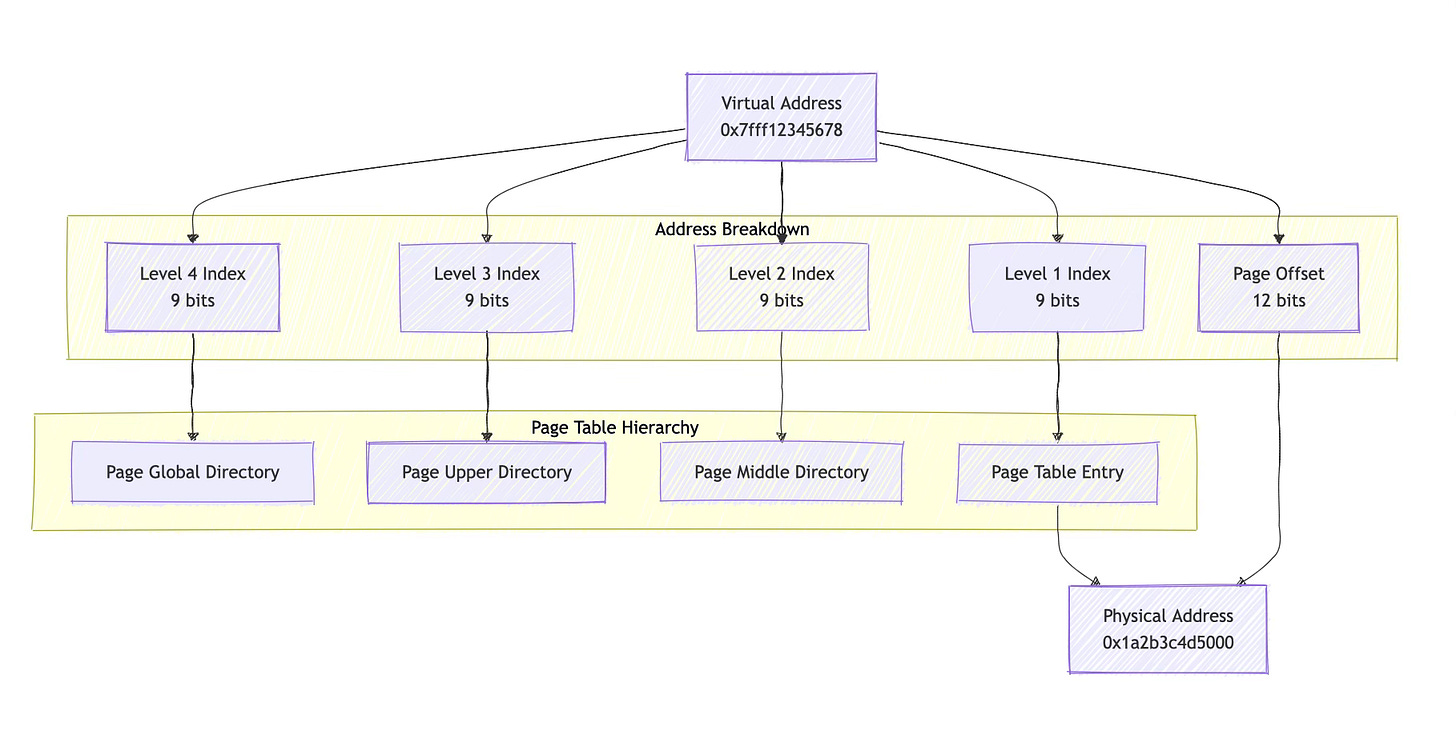

Address translation happens through a multi-level page table walk. Modern systems typically use hierarchical page tables with multiple levels, like x86-64 systems commonly use four levels, creating a tree-like structure that the MMU traverses to find the final physical address.

Each virtual address is divided into several fields. The most significant bits select entries at each level of the page table hierarchy, while the least significant bits provide an offset within the final page. For example, on x86-64, a 48-bit virtual address might be split into four 9-bit page table indices and a 12-bit page offset.

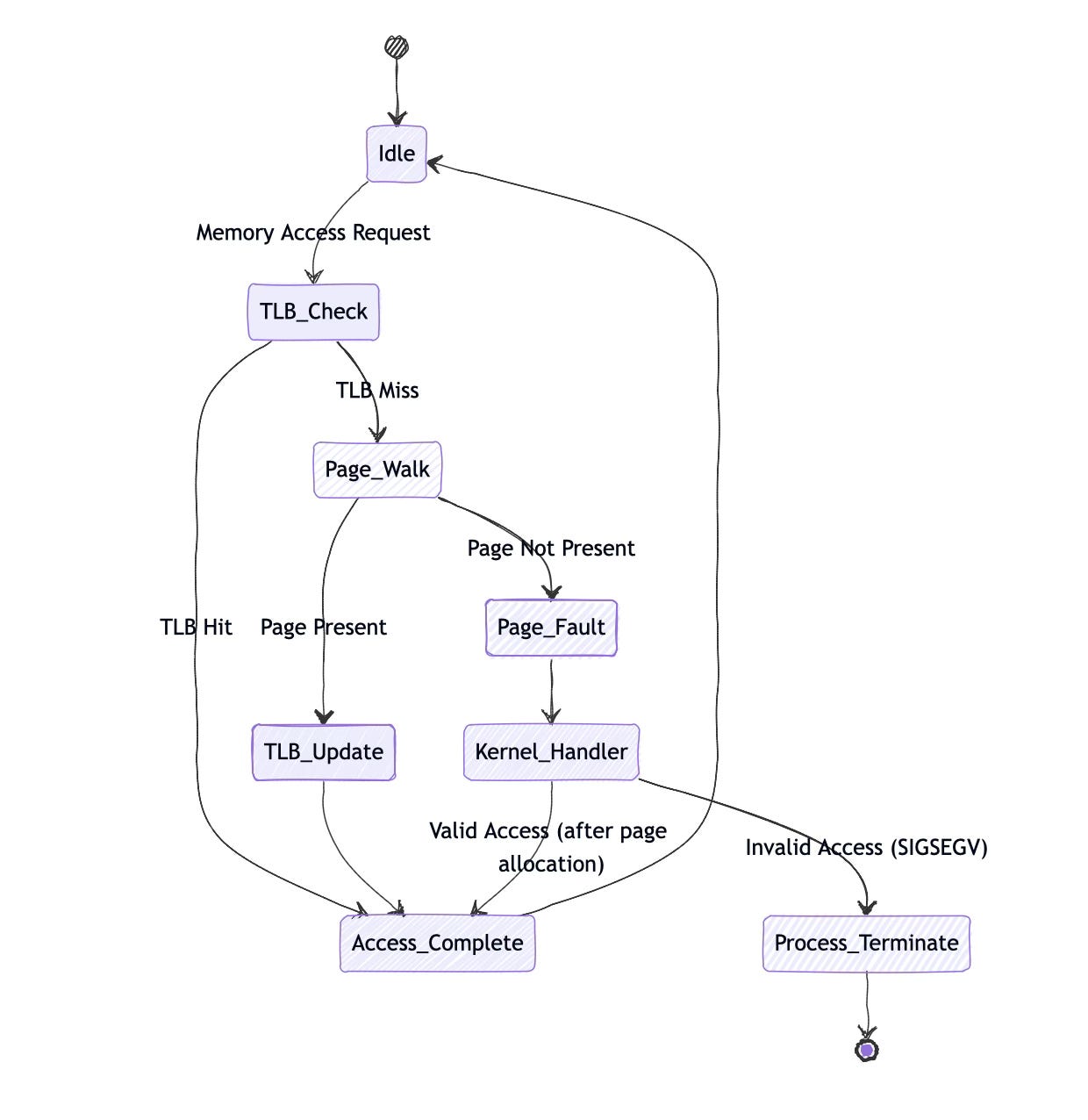

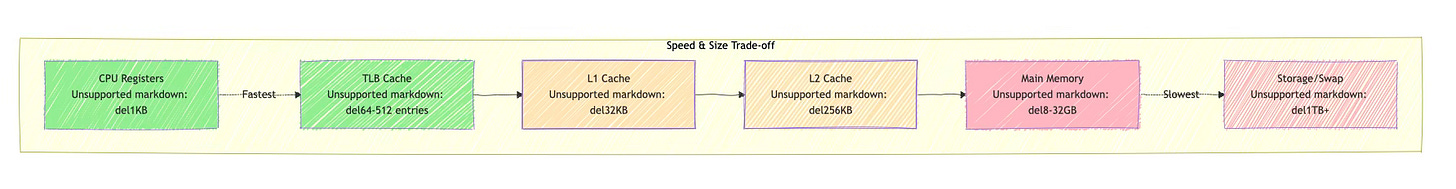

The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) acts as a cache for recently used translations. Since page table walks require multiple memory accesses, the TLB dramatically improves performance by caching translation results. A typical TLB might cache several hundred translations, with separate TLBs for instructions and data.

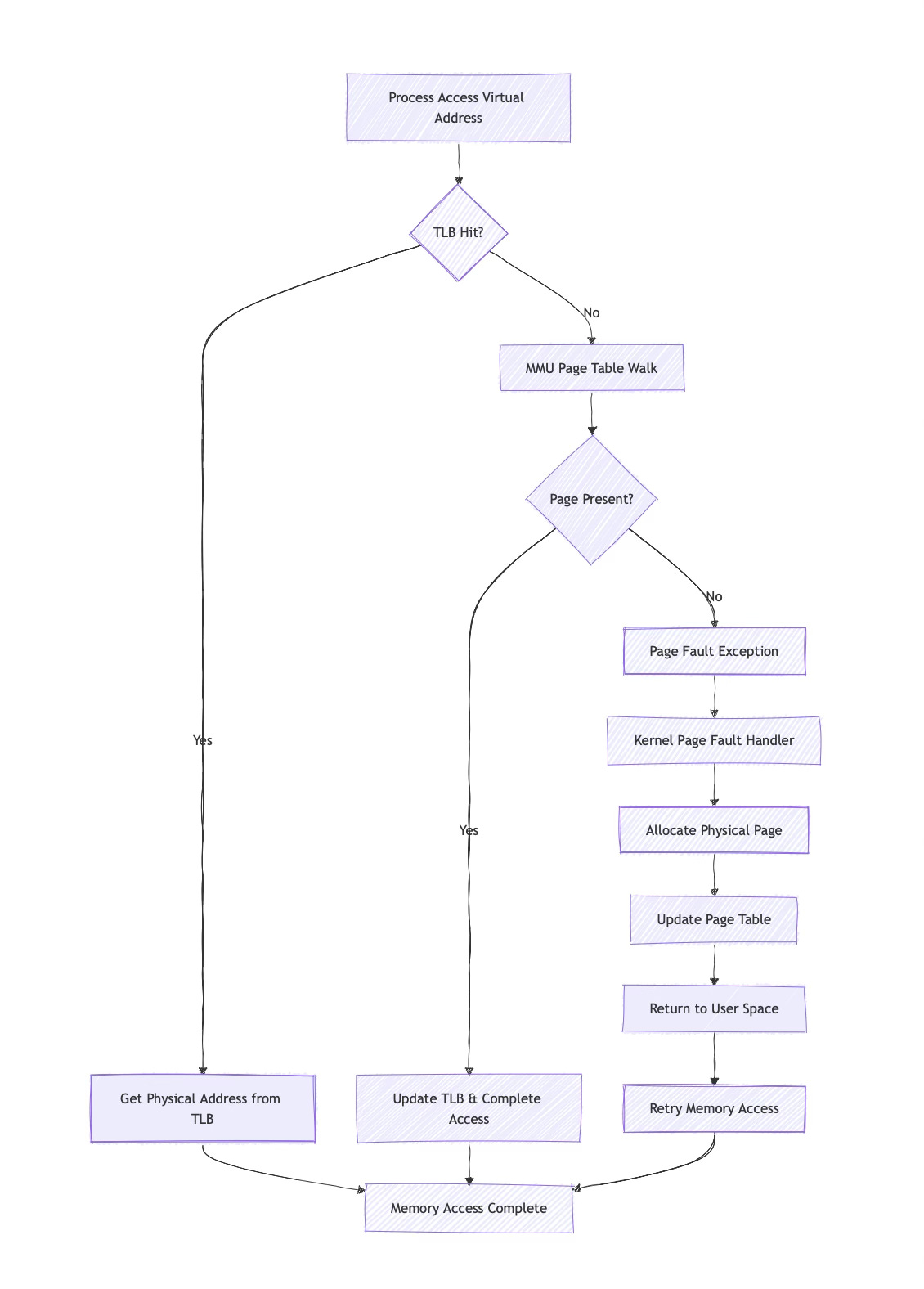

When the MMU encounters a virtual address not in the TLB, it performs a page table walk. Starting with the page table base address (stored in a special CPU register), it uses each level of the virtual address to index into successive page table levels until it reaches the final page table entry containing the physical address.

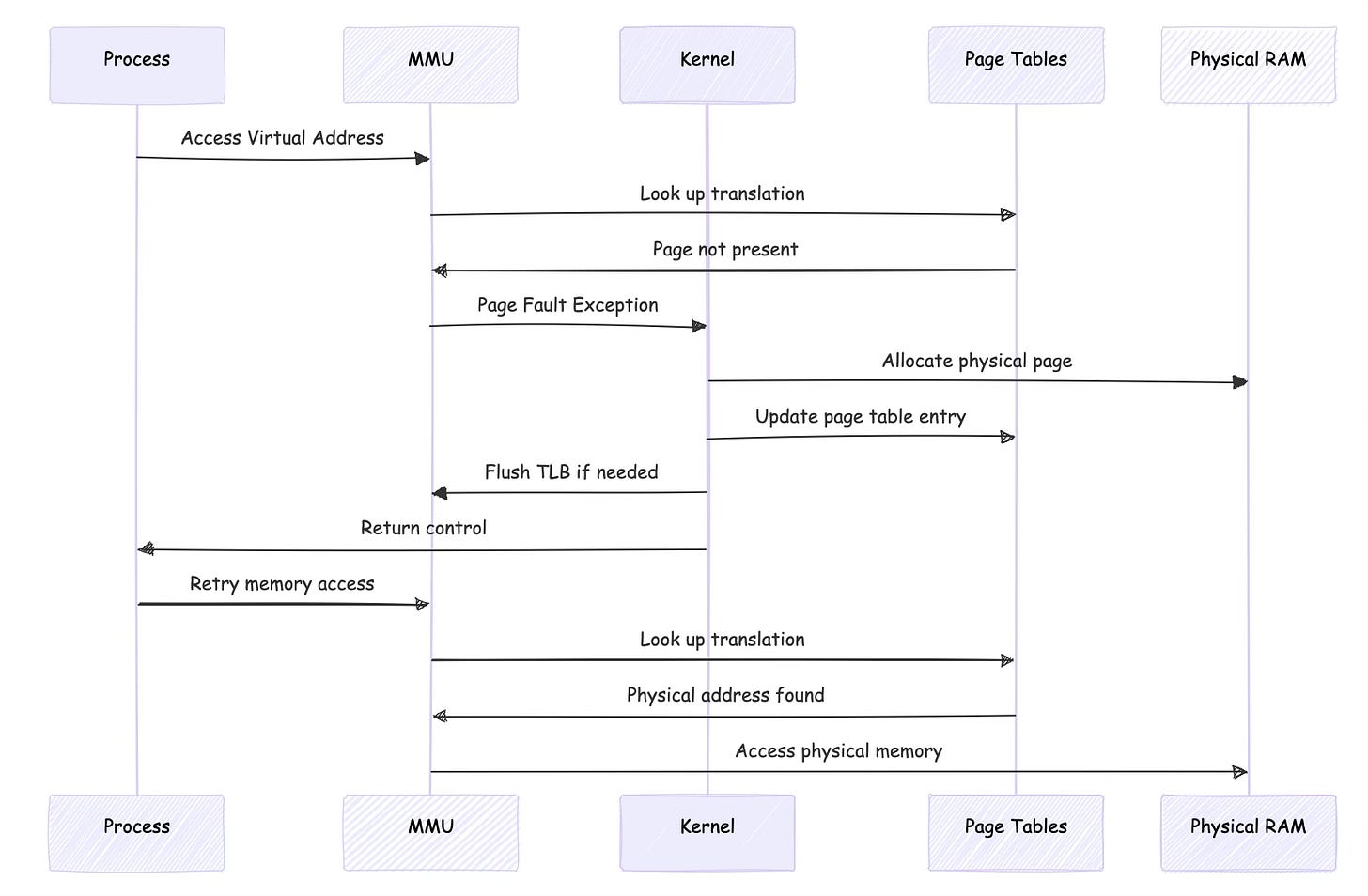

Page faults occur when the MMU cannot complete a translation. This might happen because a page isn't present in memory, the access violates permissions, or the page table entry is invalid. The MMU generates an exception that transfers control to the kernel's page fault handler.

Page Tables and Kernel Management

Page tables are hierarchical data structures stored in main memory that map virtual pages to physical pages. Each entry in a page table contains not just address translation information, but also permission bits (read, write, execute), presence flags, and architecture-specific metadata.

The kernel maintains these page tables through a sophisticated memory management subsystem. In Linux, the core data structures include the memory descriptor (mm_struct), virtual memory areas (vm_area_struct), and the actual page tables themselves. The kernel provides architecture-independent interfaces that hide the differences between various MMU designs.

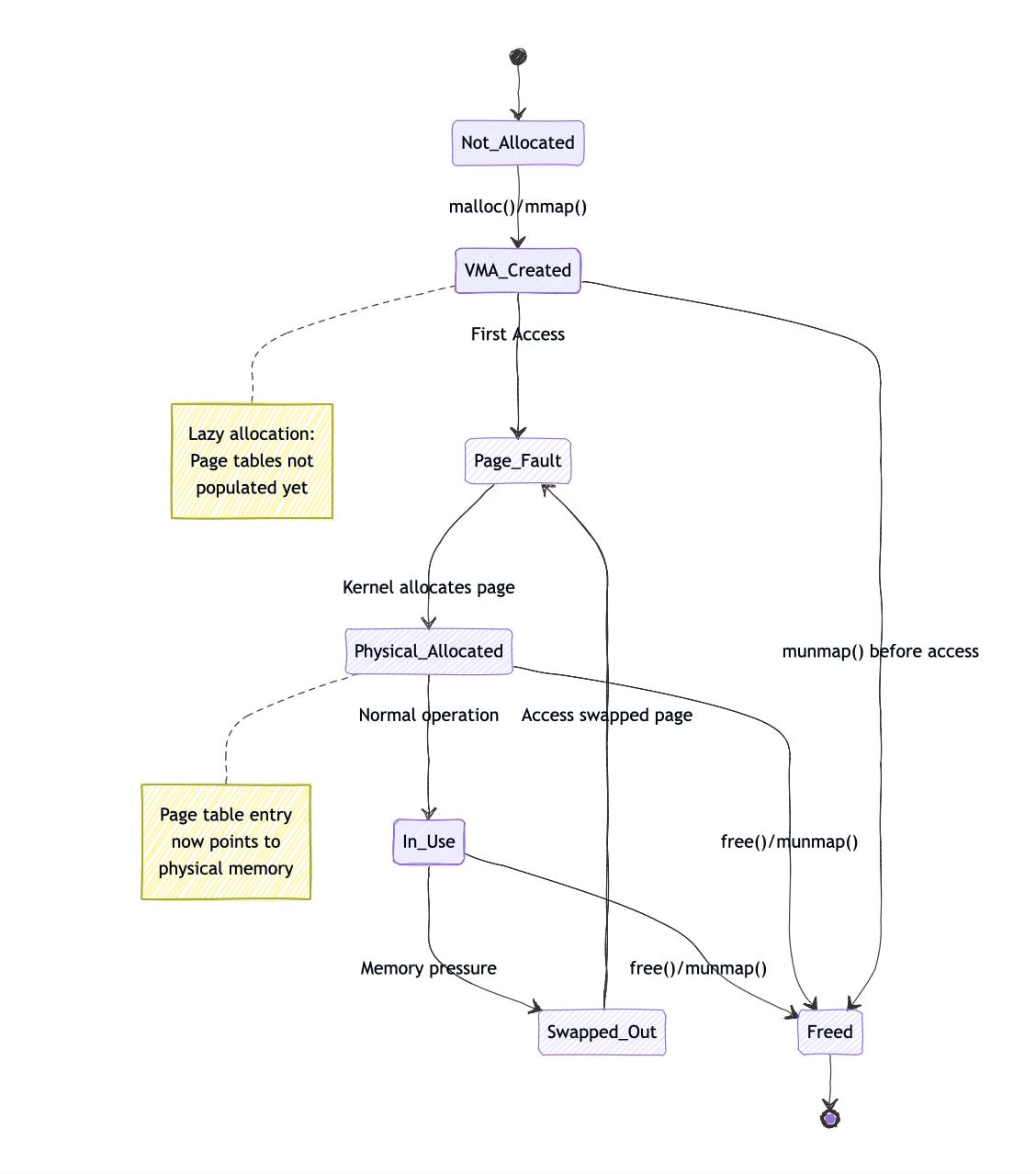

When a process requests memory through mmap() or brk(), the kernel typically doesn't immediately populate page tables. Instead, it creates a VMA (Virtual Memory Area) describing the mapping and defers actual page table creation until the process accesses the memory. This lazy allocation approach saves memory and improves performance.

Here's a simplified example of what happens during memory allocation:

// Process calls mmap()

void *ptr = mmap(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

// Kernel creates VMA but doesn't populate page tables yet

// First access to *ptr triggers page fault

*((int*)ptr) = 42; // Page fault occurs here

// Kernel page fault handler:

// 1. Finds the VMA covering the faulting address

// 2. Allocates a physical page

// 3. Updates page tables to map virtual to physical address

// 4. Returns to user space, where access succeedsThe kernel must synchronize page table updates with the MMU's TLB. When changing page table entries, the kernel often needs to flush TLB entries to ensure the MMU sees the updated mappings. This synchronization is critical for correctness but can impact performance.

Process Isolation and Physical Address Awareness

The MMU provides strong process isolation by ensuring each process has its own virtual address space. Process A's virtual address 0x400000 maps to completely different physical memory than Process B's virtual address 0x400000. User-space processes have no direct access to physical addresses, they only see virtual addresses.

However, the kernel maintains awareness of physical addresses for several reasons. Device drivers need to know physical addresses to program DMA controllers. The kernel's memory allocator works with physical pages. Kernel debuggers and profiling tools sometimes need to correlate virtual and physical addresses.

Linux provides several mechanisms for examining address translations. The /proc/<pid>/pagemap interface allows privileged processes to read page table information, including physical addresses corresponding to virtual addresses. This interface has security implications and is typically restricted to root.

The kernel uses functions like virt_to_phys() and phys_to_virt() to convert between virtual and physical addresses within kernel space. These functions work because the kernel maintains a direct mapping of physical memory in its virtual address space.

User processes remain unaware of physical addresses by design. This abstraction enables the kernel to move pages in physical memory (during compaction), swap pages to storage, and implement copy-on-write semantics transparently.

Low-Level Mechanics

System calls that manipulate memory mappings interact with both kernel memory management and the MMU. Consider mprotect(), which changes page permissions:

// Make a page read-only

int result = mprotect(ptr, 4096, PROT_READ);

// Kernel implementation:

// 1. Find VMA covering the address range

// 2. Update VMA permissions

// 3. Update page table entries to reflect new permissions

// 4. Flush TLB entries for affected pages

// 5. Return to user spaceThe mmap() system call demonstrates the kernel's role in configuring MMU behavior. When you map a file, the kernel creates VMAs and may populate some page table entries immediately. For anonymous mappings, the kernel typically uses demand paging, creating page table entries only when pages are first accessed.

Page fault handling reveals the intricate cooperation between MMU and kernel. When the MMU cannot translate an address, it generates a page fault exception. The kernel's page fault handler determines whether the fault is valid (accessing a mapped but not-present page) or invalid (accessing unmapped memory), then takes appropriate action.

Here's what happens during a typical page fault:

// User code accesses previously unused memory

char *buffer = malloc(1024 * 1024); // 1MB allocation

buffer[500000] = 'A'; // Page fault occurs here

// MMU generates page fault exception

// Kernel page fault handler:

// 1. Saves processor state

// 2. Determines faulting virtual address

// 3. Finds VMA covering the address

// 4. Allocates physical page

// 5. Updates page table entry

// 6. Flushes TLB if necessary

// 7. Restores processor state and returnsPractical Examples

Debugging memory-related issues often requires understanding MMU and kernel interactions. The strace tool can reveal system calls that affect memory mappings:

$ strace -e mmap,mprotect,brk ./my_program

mmap(NULL, 8192, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f8a1c000000

brk(NULL) = 0x55a1b8000000

brk(0x55a1b8021000) = 0x55a1b8021000

mprotect(0x7f8a1c000000, 4096, PROT_READ) = 0The /proc/<pid>/maps file shows a process's virtual memory layout:

$ cat /proc/1234/maps

55a1b7000000-55a1b7001000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 1234567 /usr/bin/my_program

55a1b7200000-55a1b7201000 r--p 00000000 08:01 1234567 /usr/bin/my_program

55a1b7201000-55a1b7202000 rw-p 00001000 08:01 1234567 /usr/bin/my_program

7f8a1c000000-7f8a1c021000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]For more detailed analysis, /proc/<pid>/pagemap provides physical address information (requires root access):

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdint.h>

// Read physical address for virtual address

uint64_t virt_to_phys(void *virt_addr, pid_t pid) {

int fd;

char path[256];

uint64_t page_info;

off_t offset;

snprintf(path, sizeof(path), "/proc/%d/pagemap", pid);

fd = open(path, O_RDONLY);

if (fd < 0) return 0;

offset = ((uintptr_t)virt_addr / 4096) * sizeof(uint64_t);

lseek(fd, offset, SEEK_SET);

read(fd, &page_info, sizeof(page_info));

close(fd);

if (page_info & (1ULL << 63)) { // Page present

return (page_info & ((1ULL << 54) - 1)) * 4096 +

((uintptr_t)virt_addr % 4096);

}

return 0; // Page not present

}Challenges

Several common misconceptions complicate understanding of MMU-kernel interactions. Developers sometimes assume the kernel performs address translation in software, not realizing that the MMU handles this autonomously. Others believe that page tables are part of the kernel's address space, when they're actually separate data structures in main memory.

Security issues can arise from improper handling of physical address information. Exposing physical addresses to user space can enable side-channel attacks or help bypass security mitigations like ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization). Modern systems increasingly restrict access to physical address information.

Performance problems often stem from excessive page faults or TLB misses. Applications that access memory in patterns that defeat the TLB cache may experience significant slowdowns. Understanding the relationship between virtual memory layout and hardware behavior becomes crucial for optimization.

Memory fragmentation presents another challenge. While virtual memory provides each process with a contiguous address space, physical memory may become fragmented. The kernel must balance the need for large contiguous physical allocations (for DMA buffers, for example) with efficient memory utilization.

Solutions

Effective memory management requires understanding both kernel interfaces and MMU behavior. Use mmap() with appropriate flags to control caching and sharing behavior. The MAP_POPULATE flag can prefault pages to avoid later page fault overhead, while MAP_HUGETLB can reduce TLB pressure for large allocations.

Modern Linux systems provide several mechanisms for optimizing MMU usage. Transparent huge pages automatically promote small page allocations to larger pages when possible, reducing TLB misses. Applications can also explicitly request huge pages through the hugetlbfs filesystem or mmap() flags.

Memory locking with mlock() or mlockall() prevents pages from being swapped, ensuring predictable access times for real-time applications. However, locked memory consumes physical RAM and should be used judiciously.

NUMA (Non-Uniform Memory Access) systems require additional consideration. The kernel's NUMA policy affects which physical memory banks are used for allocations, impacting both performance and memory bandwidth utilization. Applications can influence NUMA placement through numactl or programmatic interfaces.

Performance Considerations

Address translation overhead varies significantly based on TLB effectiveness. Applications with good spatial locality, accessing nearby memory addresses, experience fewer TLB misses and better performance. Conversely, applications that access memory randomly or with large strides may suffer from frequent TLB misses.

Page table walks consume memory bandwidth and cache capacity. Multi-level page tables require multiple memory accesses for each translation miss, creating bottlenecks on memory-intensive workloads. Some architectures provide hardware page table walkers that can perform multiple translations concurrently.

The kernel's page table management also affects performance. Copy-on-write semantics reduce memory usage but can cause unexpected page faults when pages are first written. Applications sensitive to latency may prefer to prefault pages or use different allocation strategies

Modern MMUs include various optimizations like page size extensions, tagged TLBs that don't require flushing on context switches, and hardware support for virtualization. Understanding these features helps in designing efficient systems software.

Summary

The Memory Management Unit and Unix/Linux kernel form a sophisticated partnership that enables modern memory management. The MMU, as a hardware component integrated into the CPU, performs rapid virtual-to-physical address translation using page tables configured by the kernel. This division of labor hardware for speed-critical translation, software for complex policy decisions provides both performance and flexibility.

Key takeaways include understanding that the MMU is hardware, not part of the kernel, though it relies on kernel-managed page tables stored in main memory. The kernel maintains awareness of physical addresses while keeping user processes isolated in virtual address spaces. Page faults represent the primary communication mechanism between MMU and kernel, allowing for sophisticated memory management techniques like demand paging and copy-on-write.

For system programmers and administrators, this understanding enables better debugging of memory-related issues, more effective performance tuning, and informed decisions about memory allocation strategies. The MMU-kernel collaboration underlies features we take for granted: process isolation, virtual memory, and efficient memory utilization.

Modern systems continue to evolve this relationship, adding features like huge pages, NUMA awareness, and hardware virtualization support. However, the fundamental principles remain constant: hardware MMUs provide fast address translation while kernels manage the complex policies that govern memory allocation, protection, and sharing.

Thanks for sharing this, very informative and well explained